Piece and Parse

226 Main, February 28 – March 9, 2025

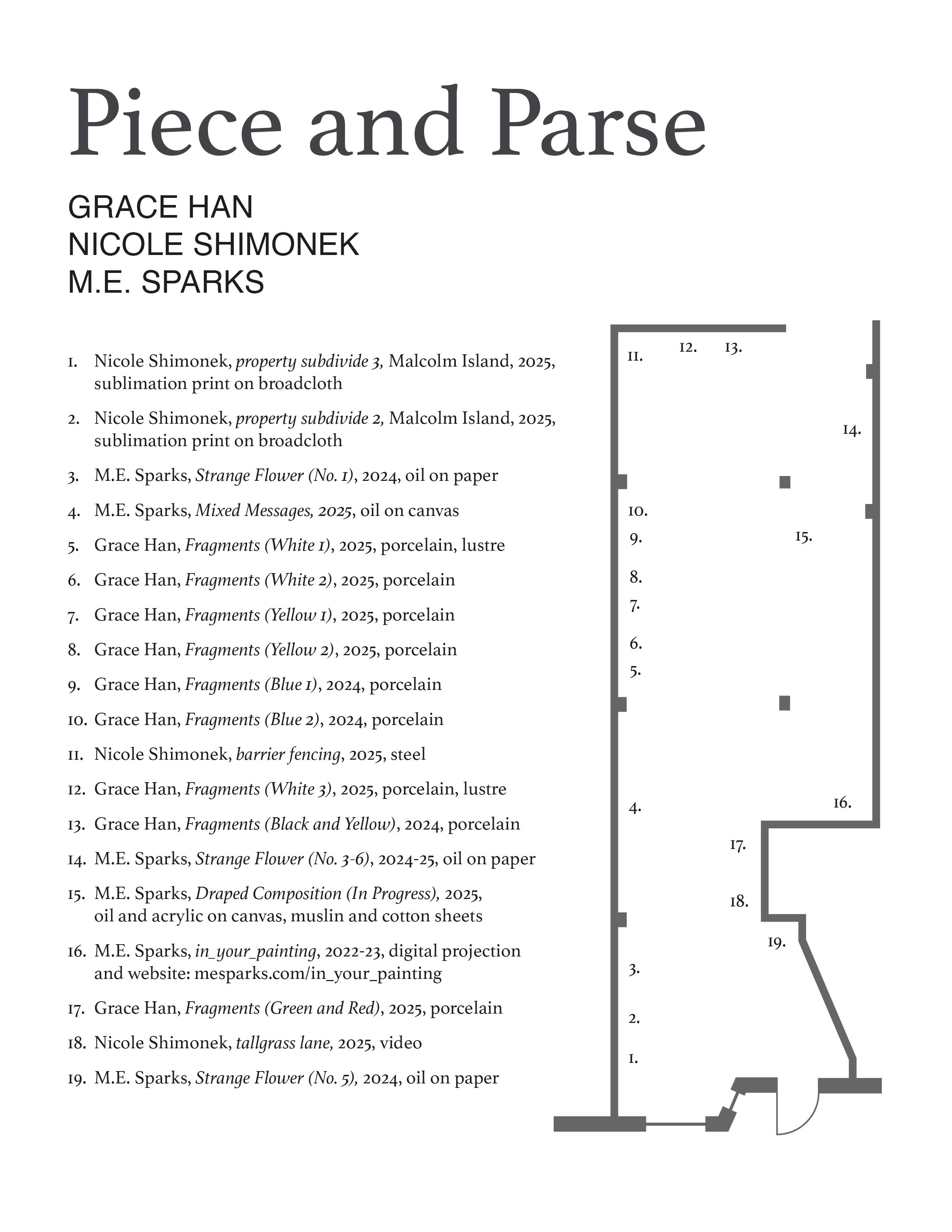

Grace Han, Nicole Shimonek, and M.E. Sparks

Exhibition essay at bottom of page

The artworks in Piece and Parse embody a liminal space, they seek to make sense of their subject matter, as well as bring peace to uncertainty. All three artists have brought the act of dismantling into their practice, they’ve taken apart narrative structures to examine fragments as individuals. Through building upon and reconstructing these fragments, stories are revealed in the rubble. From the documentation of construction sites and empty homes to the collaging and patching of our cultural history, the works exist in the in between. They don’t aim to force classification on that which resists it, but confront contradictions and navigate the ambiguous nature of identity and belonging.

— Lindsay Inglis

photographer: Sarah Fuller

226 Main, February 28 – March 9, 2025

Grace Han, Nicole Shimonek, and M.E. Sparks

Exhibition essay at bottom of page

The artworks in Piece and Parse embody a liminal space, they seek to make sense of their subject matter, as well as bring peace to uncertainty. All three artists have brought the act of dismantling into their practice, they’ve taken apart narrative structures to examine fragments as individuals. Through building upon and reconstructing these fragments, stories are revealed in the rubble. From the documentation of construction sites and empty homes to the collaging and patching of our cultural history, the works exist in the in between. They don’t aim to force classification on that which resists it, but confront contradictions and navigate the ambiguous nature of identity and belonging.

— Lindsay Inglis

photographer: Sarah Fuller

Liminal Gathering

Piece and Parse celebrates the unknown, not by trying to define it, but through its fragmentation. All three artists have brought the act of dismantling into their practice, taking apart narrative structures to examine the pieces individually. Through building upon and reconstructing these fragments, stories are revealed in the rubble.

While spending time on Malcolm Island in BC, Nicole Shimonek regularly visited an abandoned lot that was meant to be developed but got left behind amid zoning disputes. She spent time documenting the land and, aside from one encounter with an angry neighbor, only came into contact with the deer that had taken up residence.

Based in Winnipeg, Shimonek left for BC days after her mother’s funeral and returned to Winnipeg in time to say goodbye to her mother’s empty condo, after all her mother’s belongings were sorted through and packed away. Her mother’s health deteriorated suddenly and Shimonek decided to go ahead with her trip to BC as a way to process her grief. Spending time at the abandoned lot, she contemplated structures that signify residence, and how those structures are represented in times of transition. Shimonek created a metal grate reminiscent of boundaries on construction sites, placed to keep pedestrians out. The grate signifies a time of transition, hinting at a structure, but rather than offering shelter, its placement severs spaces.

Upon her return to Winnipeg, Shimonek filmed her mother’s empty condo. The footage is shown with emails from lawyers and estate agents layered on top of each other discussing the sale of the property. The overlapping text becomes incomprehensible, it’s too overwhelming to take in let alone read every word, just as it was for Shimonek to receive these messages shortly after her mother’s passing. Nearby, her photographs of the BC property create a moment of respite for viewers, while seeped in bureaucracy, the land offers a peaceful environment in which to navigate uncertainty and change.

Transitions have long been the root of Grace Han’s practice. She moved to Canada from South Korea in 2011 and used her artwork to process the uprooting of her life and the subsequent contradicting identities. In Seoul, Han trained in traditional ceramics and began experimenting with the conceptual while establishing her practice in Winnipeg. Her work examines the act of being in between something or somewhere. While she initially saw this liminality as a negative and a lack of belonging, she’s grown to view the in between as a form of freedom.

Han has transitioned from traditional ceramics to creating patchwork vessels. By piecing fragments together to create a whole, Han is integrating the different aspects of her identity into one form. Seemingly stitched together, these porcelain patches leave gaps throughout the vessel as though leaving room for the vessel to change over time with additional patching. She’s embraced the in between nature of her existence and is creating vessels that honour her identity, piecing contradictions together, but leaving room to breathe.

M.E. Sparks explores disorientation in her work, her collage paintings are at the cusp of legibility, but she’s not aiming to give the viewer an understandable image. She cuts out segments of her paintings and overlaps them on a hanging dowel. Her stretched paintings mimic the collage of the cut outs, only the layers don’t add up. The foreground and background are often intertwined, inviting confusion without resolution. Just as Han has found freedom in contradictions and the in between, Sparks celebrates that which resists definition.

She’s currently working on a video work that emphasizes the motion and changeability of her hanging works. She began the work in a residency this winter in Vermont and will continue working on it at the gallery during the run of Piece and Parse. At several points throughout the exhibition, while the gallery is closed to the public, Sparks will come in and film the work as she changes its composition. Her hanging works are already freed from their stretchers, Work in Progress is now freed from the arbitrary stamp of completion, it’s a living work that will continue to evolve throughout the exhibition. Like the land in Shimonek’s photographs, gallery visitors are seeing a site that’s not yet resolved.

Sparks further explores disorientation through in_your_painting, a hand-coded computer program that uses titles from Balthus’ paintings to generate phrases that change every time. These phrases create poetic stanzas that are visual yet don’t add up to a clear image. Phrases such as “_in your closet I searched for the liquid mirror / _in your drawer I took your arms / _and left the dandelion for later” hint at a complex story of which the viewer is only given a glimpse, allowing the viewer space to sit and accept the unknown, toexist between the comprehensible and the inconceivable.

Together, Shimonek, Han, and Sparks bring peace to uncertainty. Through taking up space in abandoned lots and slicing through clay and canvas, they’ve dismantled and reconstructed their surroundings, coming together in a gathering of liminality. - Lindsay Inglis